- The Moshchevaya Balka Kaftan

- #19: Murder Robes

- #26: Carthage Mantle

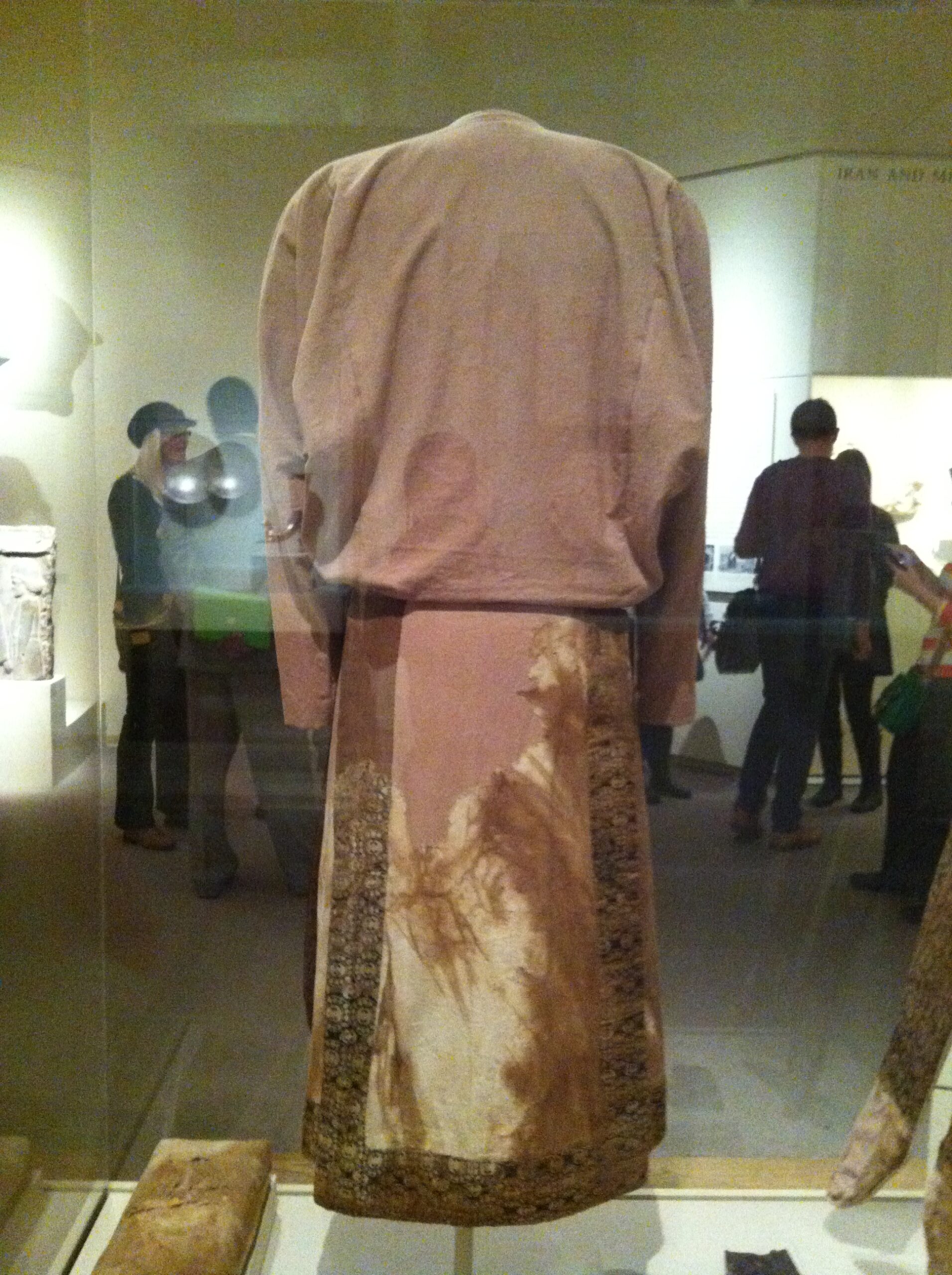

So we went to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. And we saw this piece. And Adam said something along the lines of ‘that would be awesome for Carthage’. So here we have it, this would be awesome for Carthage.

It’s really great finding pieces in a good museum to use as a basis for costume because there can often be a fair bit of information about the piece. You especially know that you’re onto a good thing when it’s displayed in it’s own case in the middle of the gallery space, like this kaftan is.

Looking it up on the Metropolitan Museum website gives me this page. And there’s just so much info there to be had. Starting off with a fantastic picture – click to get the high resolution image and examine the garment in real detail. Far better than my rubbish phone camera shots – although my rubbish phone camera shots do serve a purpose. They let me see the back and they let me remember details that struck me at the time.

The pinky-red fabric is all modern conservation, the beige fabric and gorgeous patterned trim is all the original bits of this amazing 9th – 11th century kaftan from somewhere near what is modern Turkey.

Except it wouldn’t have originally have been beige. The Met are helpful enough to have provided information about the garment to help us understand what it might have looked like when it was made. The ‘white card’ description says:

The original linen coat (caftan), preserved in part from the neck to the bottom of the hem, is made of finely woven linen. A decorative strip of large-patterned silk is sewn along the exterior and interior edges of the caftan. A minute fragment of lambskin preserved as the caftan’s interior attests to its fur lining. The woven patterns on the silk borders of the caftan include motifs such as the rosettes and stylized animal patterns enclosed within beaded roundels, which were widespread in Iranian and Central Asian textiles of the sixth to ninth century. The colors used in the textile include a now-faded dark blue, yellow, red, and white on a dark brown ground. The decorated silk fabrics are a compound twill weave (samite in modern classification) and the body of the garment is plain-weave linen. Two slits running up the back of the caftan make it particularly suitable as a riding costume.

Did you know that apparently in many galleries and museums the white cards next to exhibits have to have be the same standard as the national reading age – which is about 12 in the UK. These were only ever intended as basic info. So far from this description I know that:

- It’s made of finely woven plain-weave linen.

- It has patterned twill silk for decoration.

- It had fur lining.

- The silk has stylised animals and beaded roundels which were common to Iranian and Central Asia at this time.

- The kaftan used to be dark blue, yellow, red and white on a dark brown background.

- It would have been suitable for riding in.

But we need more!

Linked to the page on the Met’s website there are three journal articles written about the Kaftan and it’s matching leggings. The first is an introduction, the second is a genealogy study and the last is the conservators report on the piece. This last one is where the gold-dust lies. These three journal articles can tell us huge amounts about the garment beyond what the white card does.

Here are notes from the journal articles, with my own speculations:

- Other pieces of identical silk have been found – meaning that this was not an extraordinarily unusual design. It would most likely not have been for someone extremely important (like royalty or ruling class) because they would most likely have used more unique fabrics for their garments.

- The piece is most likely from Moshchevaya Balka, a burial complex that has had to contend with serious amounts of looting over the years during its excavation (which probably explains why this piece came on the art market in the mid-90s).

- The climate of the Near East means that textiles and whole garments are almost never recovered. They almost always perish because the conditions aren’t conducive to the preservation of organic materials. This means that this is one example of only a handful ever found – you can’t make assumptions that ‘all people from this area wore this kind of garment’ without other supporting evidence. But it certainly is a garment that someone in this place, at this time wore.

- Moshchevaya Balka was on historical trade routes that linked Central Asia, the Near East, southern Russia and the Black Sea. The garment could have been influenced by any of those places, or could have been worn by someone who was just passing through.

- It was made for a horseman. This is a more substantial statement than ‘would have been alright for riding horses in’. Perhaps it could have been made for a trader who would have ridden between places? Or maybe a soldier?

- We’re pretty sure they came from a burial site. People tend to be buried in their good clothes, so perhaps these were finery rather than everyday clothes?

- The survival of the silk is described as ‘miraculous’, again highlighting the fact that not many examples exist – certainly not in this kind of condition.

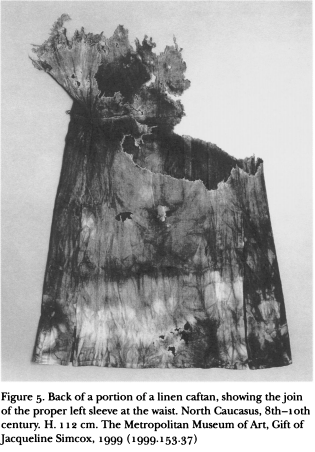

- The staining of the fabric is most likely due to the acidic material produced when the body breaks down. It wouldn’t have been some funky ancient tie-dye. Thankfully the fur lining seems to have protected much of the outer layer of fabric.

- The alkaline chemicals produced by the decomposition of the body changed the colour of the fabric. The safflower red dye (a pretty bright pinky red) turned to beige, and the indigotin blue (similar to modern indigo) turned to a grey-brown. However the brown bits have kept a reasonably true colour since they are acid sensitive rather than alkaline sensitive. This doesn’t seem important, except it potentially helps us look at other examples of textiles. Now each time we come across drab, beige colours in ancient garments we can make educated guesses at what they might have looked like before they were put in the ground for a few centuries.

- Cotton is noticeably absent from the finds in this region, indicating that this area might not have had access to it yet. Seems crazy to us today when cotton is cheap and in use everywhere, but it wasn’t always that way. If you’re trying to be authentic then cotton would not be the way forward. Linen and silk to stay authentic. Of course for LARP it’s generally about what looks cool, but you might want to stick close if you’re going for a particular look. (And this does make me want to research into what kinds of textiles would have been available in North Africa for the Carthage outfit).

- The staining on other garments examined by the conservators that were suspected to also be from Moshchevaya Balka suggest that they could be from the same body. This gives us a lead on possible under-garments for the kaftan. Here it is:

- That the conservators had several options when reattaching the fragments of materials onto backing cloth. They chose the style of garment that they felt was most likely, but still without a whole garment we don’t know if this was exactly how they would have been made.

- The kaftan would most likely have reached mid-calf on the wearer. Perfect for a fighting garment for a

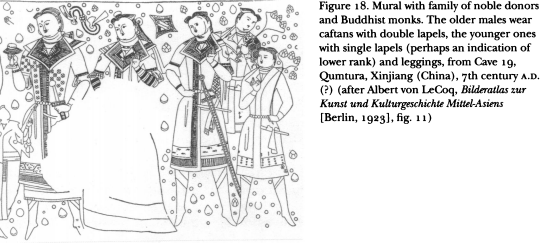

bloodthirstywell-mannered Carthaginian. - Other representations in art of the steppe people suggest that this Kaftan could have been worn with a plain linen version underneath and a sheer but decorated kaftan over the top. When it was cold there could have also been a fur kaftan outer layer, along with accessories like belts and mitts. And boots. I love boots. But apparently layering was cool way back when and we weren’t the first to invent it.

- The triangular side pieces on the front cause the side seams to push to the back, consequently narrowing it in at the waist and essentially making it a fitted garment. This causes the sleeves to look like ‘wings’ on the back, but they give huge amounts of movement in the upper body – suitable for a rider.

- The sleeves had narrow wrists, probably to retain heat. Which is good for a Carthaginian in modern England.

- There are two long slits in the Kaftan below the hip line to enable movement in the lower body. While standing they would reveal the leggings a little, but while sitting on a horse or crouching they would reveal all of the decorated legging. This needs fixing and turning coolthentic rather than authentic – the Carthaginian will be wearing leather trousers under it. But I have a plan.

- It used a triple button and loop fastening – picture in my camera phone pictures above.

- The fact that the fabric was found to be cut from a pre-woven bolt, cut with immense skill and then sewn together finely indicates that this region was above average in it’s textile culture. Perhaps it would be erroneous to take this as an example of garments from the wider area at this time.

- The linen making up the majority of the garment was white – as can be seen on the back shot above.

- The large, decorative borders of fabric have been used in a previous garment. This could indicate either some sentimentality, or perhaps a thrifty owner who had the clothes remade into a newer and more suitable or fashionable style. It’s therefore unlikely that this would have been owned by someone very high status.

- Collar and cuffs are unknown. They could possibly have been in existence, they could possibly have been made from the same fur as the lining.

- The warp of the linen travels vertically downwards on all pieces when the kaftan is laid out flat with the arms outstretched. Including the lower arms. This may not have been an effective use of materials, which indicates some wealth.

- There’s no seam along the top of the wrist to shoulder line. The fabric was cut on a fold here.

- The seams were mostly flat felled seams, stitched towards the centre units.

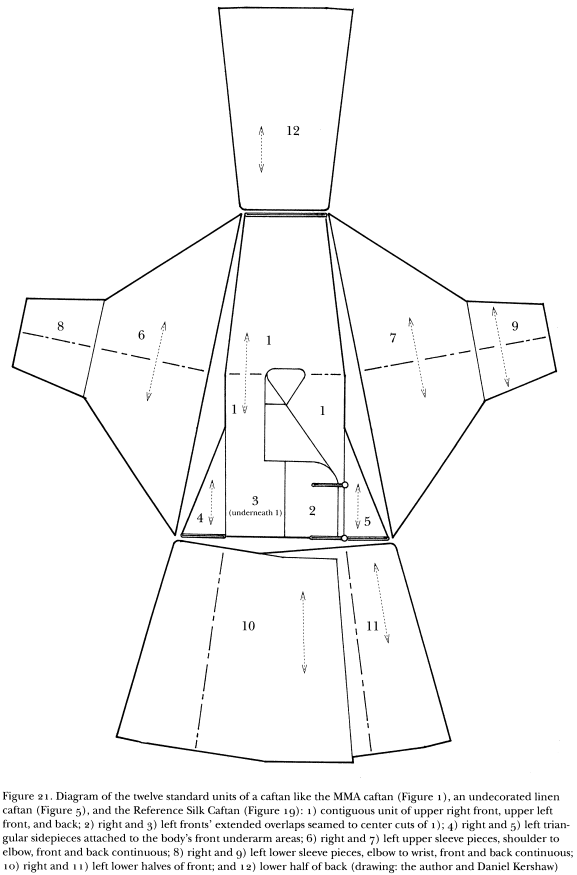

- And then of course we get the really precious part of the journal article for making a replicaish. An actual diagram of the pieces that made up the reconstruction on show in the museum:

- It was likely to have been constructed by piecing together the top half of the garment and then following that by attaching the bottom half at the waistline..

- There are notes about how the front panel was put together. It was slit up the front and a neckline cut out, then extra panels were attached (2 and 3 in the diagram above) to make it double breasted.

- The side pieces – 4 and 5 above – are the aforementioned gores that push the side seams to the back. Take note here – the length of the side seam on the back part of piece 1 must be the same as the length of the front of piece 1 including pieces 4/5. That means the front of the garment could be shorter than the back – this requires a calculator and some Pythagoras. Presumably this is made up for by the fact that 10/11 are likely to be longer than piece 12, but it will look strange to modern eyes as we would expect the waist seam to fall consistently all around the body rather than being lower at the back.

- The sleeves are two separate pieces which might give the opportunity to insert decorative fabric or embroidery or something. On the original it is most likely that the lower sleeve portions would have been pieced from various offcuts. Thankfully fabric isn’t that scarce now since it’s all made by machine and I won’t be doing this.

- There are instructions for sewing on the lapel within the journal. Basically sew the piece to the outer edge of the garment, fold it back, turn the edge under and sew it to the centreish of the garment.

- It’s unknown if there would have been a decorative neckline.

- The two front panels extend around the body by 7cm due to the extra inserted panel. This indicates that this garment would have been reasonably close fitting rather than baggy. The ability to move comes from the extra space generated in the back due to the inserts and the splits in the side seams for leg movement.

- The front panels were seamed to the back panels down to the hip line (might want to make it waist line if I make a version for myself).

- One fastening inside on the right, one outside on the left and one on the breast on the left.

- Because the fur lining didn’t extend to where the silk decoration was continued inside the kaftan, a layer of wool wadding was inserted here to maintain the thickness and drape. Worth considering if I make a thicker, lined version.

- The dyes were poor quality in nature, perhaps indicating that the silk was at the cheaper end of the scale for what it was.

- It also appears that the weavers were in a hurry (due to tension differences in the material) which again indicates that this could be a cheaper silk than average.

- Female garments found in this area seem to take inspiration from Eastern Mediterranean culture, while male garments are often based on Eastern or Persian culture.

- Here’s an example of how it would have been worn – especially around the neck area.

So then I finished off by taking a quick look through the Vecellio book of costume (from the 16th Century and before) and there’s a remarkably similar garment in the Persian section, illustrating a soldier. Unfortunately Vecellio doesn’t make any comments about the kaftan, only the armour and the horses tack that he would wear. But it does reinforce the idea of kaftans as riding garments. I also really like the way that the front flap is fastened up to the belt. That might have to happen for fighting and stabbing.

There are also similar garments in the Hungarian and African sections of the book, although they tend to not be asymmetrical closures like this one.

So what have we learnt…

- That we have evidence for this kind of garment in the 9th-11th century, the 16th century and in relatively modern times. It’s entirely possible that it extended out way before the 9th century too, making it almost certainly suitable for Odyssey. While I’m adapting this for the Cartheginians it would also be really good for the Persians.

- That it would have been made for someone who was a rider. Could be a trader or a soldier. The amount of movement makes it quite likely it was a soldier.

- That it could potentially appear anywhere along the trade route from East to West, but it most likely was a garment that originated in the Near East.

- It wasn’t an overly high cost garment. It was nicer than ‘basic’, but not extravagant.

So there we have it. Time to make the pattern pieces!